A Conversation with Jenny Whidden

Jenny Whidden is a writer from Rolling Meadows, Illinois, with a background in climate journalism. As a reporter, her work has been published in the Daily Herald, Chicago Tribune, and others. Jenny is also a co-host of Poets’ Club of Chicago. She lives in Chicago with her PC and her black cat, Princeton.

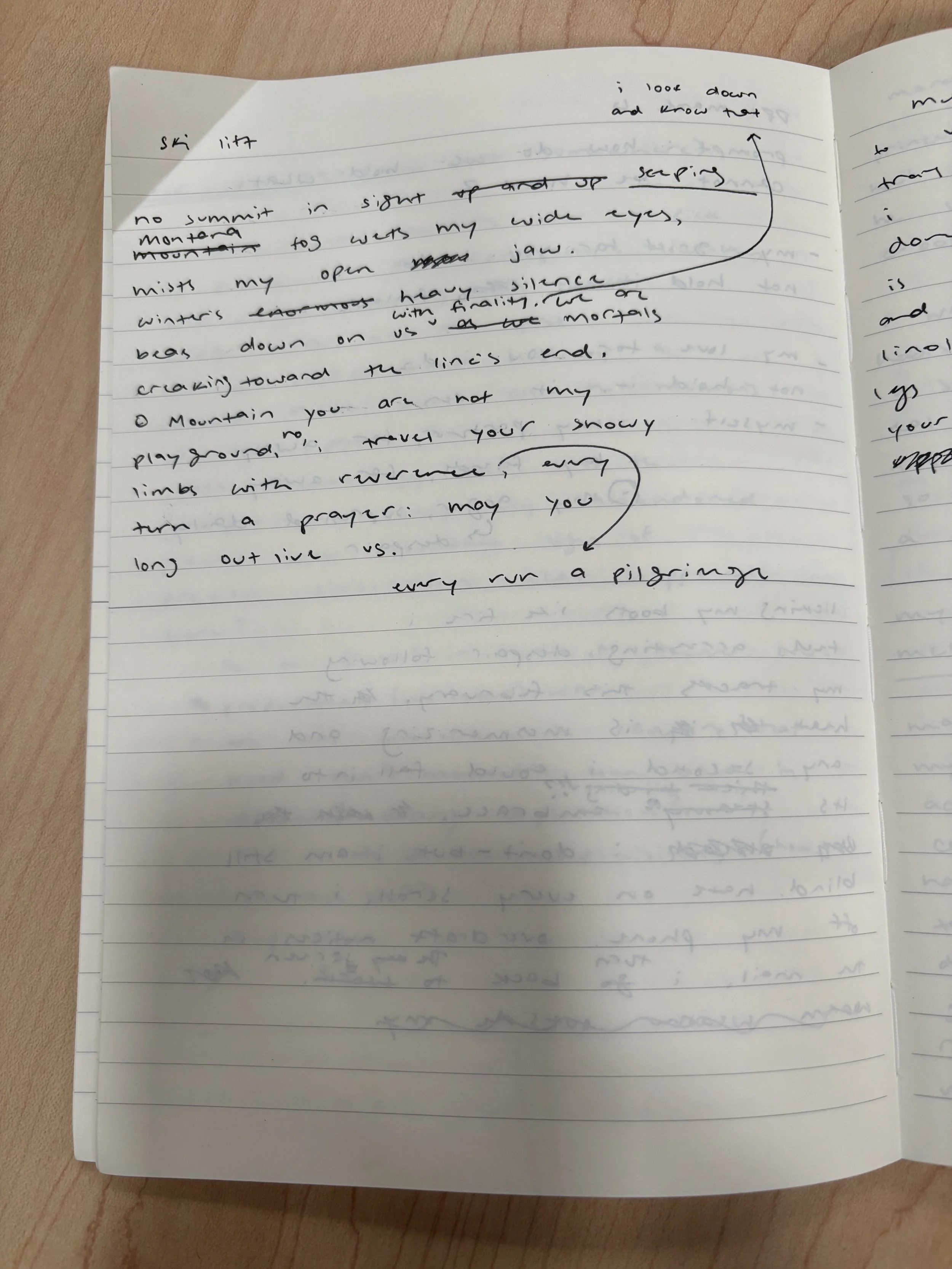

“Ski Lift” paints a landscape à la the wisdom of Whitman while our speaker celebrates the ubiquitous beauty of nature and our relation to the world as ephemeral beings.

“Dinner Party” explores the speaker’s journey of reconciling an unpleasant truth of dialectics: tragedy is part of life.

“Missy” details an uncomfortable night in an unstable home. While a couple’s problems boil over out of the room in the form of sobs and shouts, the scene evokes memories of the speaker’s childhood during which they may have endured similar situations. The poem ends with kindness amidst hopelessness as the speaker feeds the starving cat, a small kind act to the animal that must endure these altercations and the precarity of the household that produces them.

Jenny’s poems, “Ski Lift,” “Dinner Party,” and “Missy,” can be read in Issue no. 1 of Sabr Tooth Tiger Magazine.

Note: Test Literary Series is a regular reading event here in Chicago in which four authors of poetry, short fiction, non-fiction, novels and more share their work in front of an audience, who, in turn, provide feedback and critique on the works. Written on a Napkin is a regular reading at various locations in Chicago. They also published their debut zine in the summer of this year.

“It is fun to go through your old drafts because you see what could have been . . .” —Jenny Whidden

Juan: When did you start writing, and what role does it play in your daily life?

Jenny: I started writing daily, poetry-wise, last year. Originally, I was interested in doing more fictional short stories. Eventually, I wanted to lead up to a novel, which maybe down the road I'll get back into. I didn't know where to start, so I went to Test Literary Series to see what that event was about. I wanted to expose myself to more writers in the city, and I heard poetry aloud for probably one of the few times in my life; I hadn't been that exposed to it previously, and I thought it was awesome. I started writing poetry then.

That was probably early 2024, and I learned by experiencing. I really didn't know too much about what I was doing, but the more I did it, I felt I would just figure it out, which turned out to be the case. I saw Written on a Napkin was looking for readers in the summer of 2024 and I knew that if I signed up, it would light a fire under my butt to get some more work done and to take it more seriously.

That's actually my primary motive whenever I sign up for a reading, because I know I'm about to start writing like crazy. I would say, honestly, the poetry communities in Chicago have played a huge part in the development of my poetry—the inspiration and the motivation.

Jenny reading her work at Written on a Napkin’s one year anniversary event, 2025.

Juan: What got you interested in writing prose before you shifted to poetry?

Jenny: Since I was a kid, I had this romantic idea of being a writer, and I enjoyed books a lot. I was one of those bookworm kids. My parents were always yelling at me to pay attention more because I would always be reading. I remember one time, my dad actually took my book out of my hand and threw it because I wasn't paying attention at all, which was kind of mean. You know how parents can be…

That's a long winded way of saying I loved books, so I wanted to try my hand at it. Every once in a while, when I had time growing up as a teenager, I would jot down ideas for stories. I also really love school, so I loved writing for school. That was the primary reason.

Life gets so crazy when you're growing up—you're so busy. I think I was more busy as a kid than I am now. We had to be in school for X amount of hours a day, I had to be in X amount of extracurriculars. Then you go to college, and I always felt very overwhelmed. Coming to Chicago and just having my life to myself, I thought, “This is it. I finally have time to write.” That's when I found poetry.

Juan: How long have you been in Chicago?

Jenny: I've been in Chicago for three years this summer, so it would have been January 2023 that I moved here with my roommates—one of them I've known since high school.

Growing up in the suburbs, everyone wants to go to Chicago. I wanted to be different, like, “I'm not gonna go to Chicago like you kids. I'm gonna do something different and cool, like go to New York City or LA.” But I went to Milwaukee for college, and then I got my first job in New Hampshire, and I encountered a very lonely time in my life. I didn't know anyone, and I was doing a full time job that was difficult for me and my skill set, and I had a really hard time. During my time in New Hampshire, I thought, “I want to go live with my friends and my sister and my mom, and they all live in Chicago. Chicago is the place for me.” And thank gosh I did because I love it here. It's so awesome here.

Juan: Do you still work in that same industry?

Jenny: No, I do something a little bit different now. I used to do journalism. I was an environmental reporter, and then the funding for the position that I had ran out, so I needed to find a new job. I really wanted to stay in journalism, but my bank account was dwindling, so I started looking at other positions. Now I'm working in PR for the state government. It's for an independent agency, and it has ties to renewable energy. That was part of it that drew me because I knew that I had a background in energy from doing climate reporting.

It did feel a little bit like I sold my soul to leave journalism for PR, but it is a common pipeline. Journalism is a difficult industry, and honestly, the free time that I got did lead me into poetry. Because journalism is very stressful, it also took up a lot of my writing heart.

When that freed up and I wasn't so worried about the bills because I was getting paid better and had more creative energy, that's when I really started writing poetry. I read at Written on a Napkin when I was unemployed looking for a job. Having that time off of work, even though I was so sad to leave journalism, it definitely segued into poetry. I don’t know what my life would have looked like if I had stayed in journalism. I don't know how much I would be doing poetry now.

Juan: It sounds like you're still doing something around renewable energy, which I would imagine is still important, and it doesn't sound like a very sell-your-soul type of role.

Jenny: Yeah, that was one of my goals when I was applying to those other jobs that weren't in reporting. I didn't want to work for a for-profit corporation that was selling something. I was applying to environmental-related jobs because I wanted to keep a little bit of that passion. I can be a very idealistic person. I don't think I would last in a corporate environment, because if I was, I would probably become a shell of myself—not to sound very dramatic. Honestly, I understand people who do it, but I think it would be too difficult. When working for a for-profit company, it really depends on the content as well. What you're selling and what you're doing, I could see it being fulfilling.

There's always something happening in journalism—you have to make money. I remember when I was an intern in Milwaukee for one of the big papers there, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, one of my first assignments was doing a story on this woman who was attending her sentencing hearing for feeding her daughter and her friend's pot brownies. Obviously, it's interesting, but I remember feeling uncomfortable and going to my editor being like, “Why are we writing this story? Why is it helpful?” And he said, “Well, it's good to build awareness about the dangers of weed brownies, you know?” I knew the real answer was, “This is a clicky headline that will get a lot of interest.”

Even though that wasn't necessarily a negative story to do, I felt at the time—especially when I was younger—that everything I did had to be for a greater democratic purpose, so I hated doing those stories. That's why I loved climate journalism. It was so directly useful; I felt like I was using my time and my energy and my writing to raise awareness about really important things. Sometimes I really miss it, but that's why I love writing about nature and about climate issues in poetry.

Juan: I was gonna mention that as a tie back to “Ski Lift.” Your passion for nature shines through. Have you always felt that way, and is nature one of the things that inspires your journey into poetry?

Jenny: It definitely is, and coming into poetry while having to say goodbye to journalism influenced my nature poetry as well. In doing climate reporting for two plus years, I learned a different perspective, but I always loved nature. Honestly, who doesn’t? It's so beautiful and wonderful to be in. I think everyone, even if they don't like being out in the bugs, can appreciate a walk in the fresh air.

I do think learning to have a greater appreciation for our environment enhances life. The concept of the environment expanded for me to encompass our material goods. I started seeing everything that I held and bought as organic material that was somehow made into X thing, and that was also made into that thing using energy and labor. I saw everything as a cycle of creating things using the resources that the Earth gives us.

In this current era of hyper-consumerism, I really needed that perspective. I never truly saw things we buy for what they are. That lends itself to my reverence for nature that is seen in “Ski Lift.” You know, there's a little bit of a religious tone in that poem.

Juan: Did you grow up religious?

Jenny: I did. My mom was Baptist, Christian. I don't know how much I ever really bought into it. I love singing in church because it's fun to sing with a big group of people, and you feel that belonging. But I never really felt, personally, very religious. I think I just enjoyed going to church to socialize with people and to dress up and look cute. I've never subscribed to a religion, but I'm certainly not an atheist.

When I was in high school, I was super atheist, though. I was like, “We die, we see black holes, and that's it.”

Juan: That seems very teenage, yeah.

Jenny: Oh, my. I was so adamant about that. I remember one time, I made my best friend cry because she was Catholic; she believed that all her dead relatives were in heaven, and I was like, “No, they're not. They're just dead,” and she cried, and I didn't give a crap. I was like, “She needs to know. Stop buying into this!” But now as I got older, outside of high school and probably through late college, I began to accept that I didn't know everything about the world like I thought I did.

Juan: I have some insight from the poetry club, but I am curious how you develop a poem from start to finish. What's your typical process of writing from inception to final product?

Note: PCC is Poet’s Club of Chicago, a Discord server/writing group co-hosted by Jenny and another Chicago poet, Michelle Glans.

Jenny: I typically start with jotting down ideas in my notebook, or on my phone if I'm running around, and save them for when I have some quiet time to myself. It's funny because Michelle at PCC told me that when she feels the idea for a poem, she needs to get it out then and there, and she'll be riding on the bus, on the treadmill, you know, wherever she is. I thought that was funny because I'm the opposite, in that I feel like I need to wait for a special, calm moment where I can really write.

I have a huge list of ideas. Sometimes they're lines, or sometimes the very raw form of the idea. Typically, I schedule out my writing nights when I'm being the “best” version of myself. I schedule all my writing nights because my weeks get filled so fast with hanging out with friends and my other hobbies, so I've learned that I really need to set aside that time, as if I'm scheduling a date with a friend.

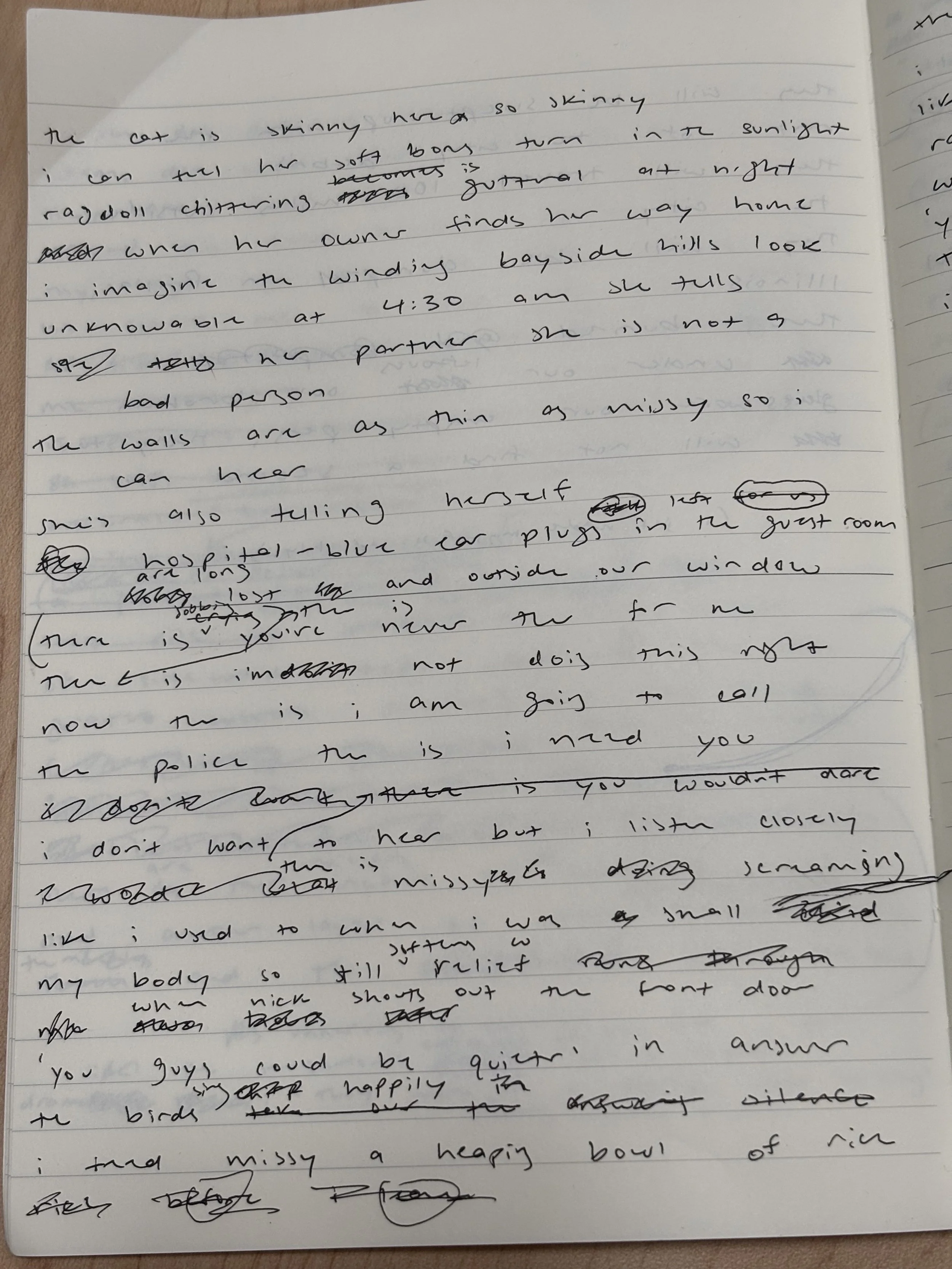

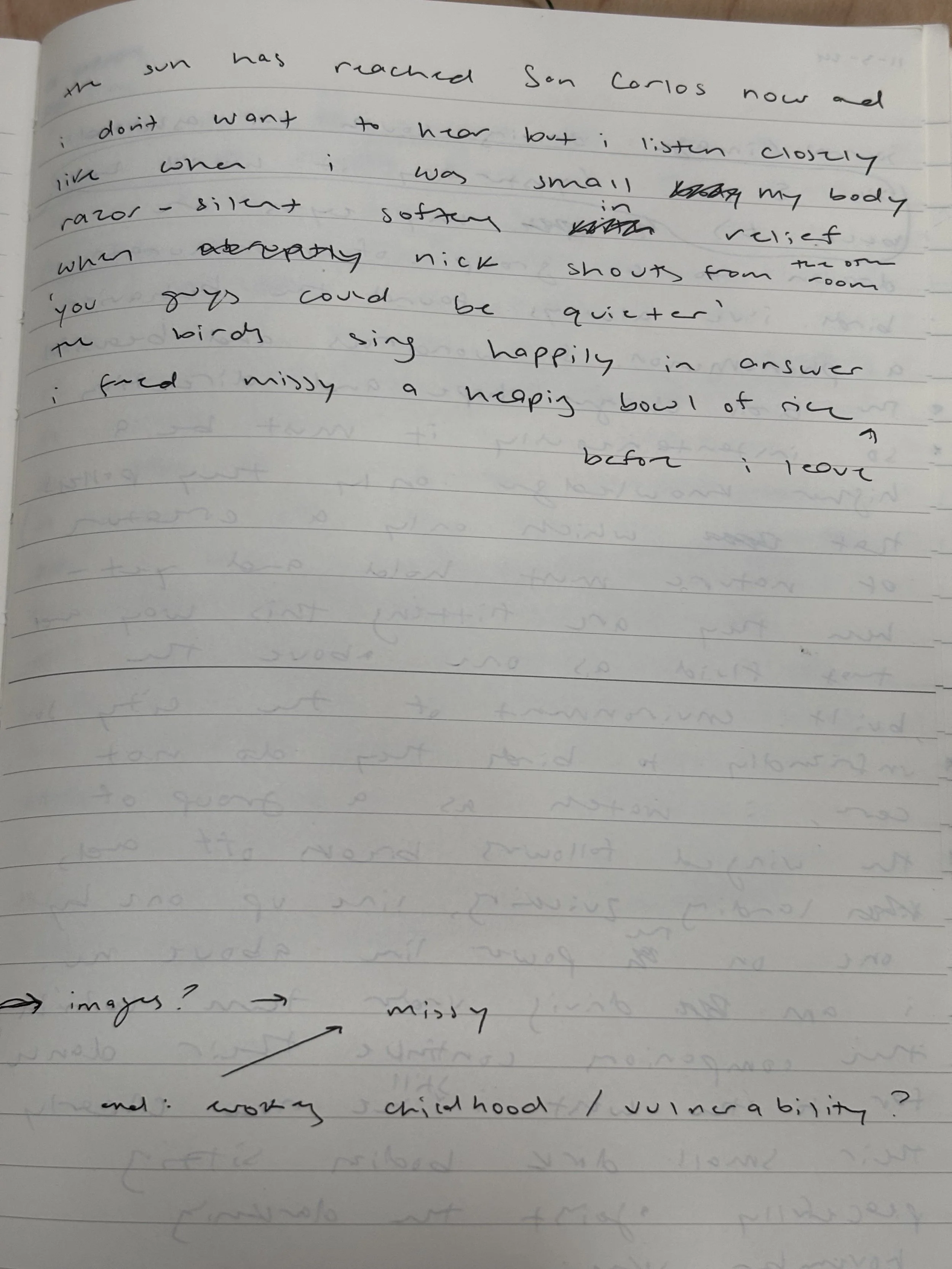

Usually I'm at my computer, or I like to go to a cafe, and then I just write. It usually turns out like this: this is “Missy,” this sort of scribble. And then there’s “Ski Lift.” I really like pen-to-paper. It feels so nice to put pen to paper.

Juan: That's always nice, right? When it just flows out?

Jenny: Yeah, usually I would say it comes out messy, but something about it feels poetic to write ink to paper, way more so than typing on my phone or my computer. I start on the page, and then I scribble out as much as I can, and usually there's a lot of arrows. Once I feel good about it, or if it's gotten too messy and I need a cleaner copy, I move it onto my PC, and that's where a lot of the final editing happens. Often, if I feel like I've done all of that and I don't feel good, I go back to the notebook, and I open a new page and try again. If I'm really stuck and everything's bad, I either step away from it for a while, or I do a freewrite journal entry about the idea to try to access my feelings about it. I've always kept a diary since I was young. I feel like that's a good way for me to explore emotions and ideas.

Juan: That's a good idea, like the metacognition aspect of it?

Jenny: Yeah, because sometimes I feel stuck trying to create a really excellent poem, and I lose what I'm feeling or saying.

Juan: Do you feel that there's a heart of poetry, or something that makes a poem a “good” poem? What do you think that is?

Jenny: I feel I've written a good poem when I've discovered some truth for writing. I often feel like my ideas are questions or fragments of some thought that I need to explore, so when I've completed a poem, it's when I've reached that feeling of, “Oh, that's what I was trying to say, or that's what I was feeling.”

Juan: It's very processual—processing.

Jenny: That is how I view it, but I also think it is about truth a lot for me, too, and I think that's due to my time as a journalist. Everything that I write, even if there's some fluff in there that didn't necessarily happen, I want everything to feel very true. Whatever that might mean.

Juan: It's a bit of that Faulkner saying, "The best fiction is far more true than any journalism."

Jenny: One hundred percent. I feel like all creative people can feel that way. Anyone who loves movies or fiction can feel like something's really true, even though it's fictional.

Juan: How do you determine how to strike the balance between the field generated by the sound of words and the meaning of the words in context? One of your poems made me think of “Medusa” by Sylvia Plath in terms of the way the sounds of the words themselves felt very much the point, almost as much as the meaning of the phrases and narrative that employ them.

Jenny: Ideas are the core of my writing. The sound comes later, and sometimes that's why I really have to push myself to think about the sound and the context. That balance is constantly thinking of the poem as vocal performance rather than being read on the page. That's probably really influenced by how I started with these local reading series in the city.

Anytime I'm writing—even if I've just written three lines and I'm still in the middle of writing it—I read it out loud as I'm going, so I can make sure that that sound also is giving the feeling as the meaning of the words. For instance, in Missy, “The sound of ragdoll chittering is guttural at night.” It's a little harsh. “Chittering, guttural.”

As soon as I wrote it and I said it out loud, I felt satisfied with that feeling, but that's something that I feel I'm constantly working on—making sure that I'm paying as much attention to the sound as to the meaning. I can be a little bit imbalanced in that way.

Juan: In “Missy,” you express a connection with Missy the cat that alludes to your self-perception, and that creates an interpretation of the poem as a connection with and healing of your inner child. Do you find poetry therapeutic? And is it more about creating something new and beautiful, or doing inner work to connect with and heal yourself?

Jenny: It's definitely both. I definitely find it therapeutic, and I do think it's healing.

It goes back to that idea of finding some new truth, though, and the process of discovering that truth is therapeutic in itself, and on the way you get to create. Sometimes, it's something that you want to share with the world, or at least that is a big part of it to me.

It is the best feeling when someone comes up to me and says, “That hit me so hard. I loved that line. I knew exactly what you meant,” and that sort of human connection when sharing my writing is so fulfilling. There's inner healing and inner connection, but there's also that interpersonal piece of it that is really in the text as well.

Juan: It ties back a little bit into that idea that poetry is meant to be performed and spoken out loud, right?

Jenny: It's interesting to have my work published; I'm not that experienced with having it published.

I had a few poems in the Written on a Napkin zine, and now this, and it's funny, because I'm not used to sharing my poems on the page. It feels like you're letting go a little bit—because it is! It’s a different delivery, for sure…

It's awesome, too. I really like it.

Juan: Definitely a surrendering.

Jenny: Of control a little bit… of how you want to communicate the poem.

And that's when the words really have to stand for themselves, because there's so much pizzazz and extra cues that you can give in a performance that we all know are lost. The words are there, bare for all to see, which is also lovely in its own way.

Juan: Have you been playing at all with presentation on the page, as a means of saying, “This is specifically for print, so let me think of how I can have that same sort of influence over the reception of the words themselves”?

Jenny: Looking at the three poems for Sabr Tooth… I know I used italics for quotes in “Missy.” I don't think I used any other sort of formatting, but certainly the punctuation and the line breaks, trying to encourage pauses where I would but other than that, honestly, I just let it be.

Formatting is also something that I am constantly experimenting with, seeing what looks or feels right in the moment. Of course, learning from reading and listening to other poets is so important, and I need to do more of it. There's nothing like the feeling after going to a reading or reading a new book that really spoke to me that makes me want to go and write.

Juan: Do you have any other projects going on, or any other things you want to put out there?

Jenny: The only thing I would plug is the Discord writer’s group, @poetsclubofchicago, if you were looking for some writing buddies in the morning or evening.

I really enjoy running it. Michelle and I got it off the ground in March, so it's still kind of a baby project to me, and we're experimenting with it. I really love the idea of writing with other people. Like I mentioned, it is accountability, but it's also about habit and building connections with other poets. Check us out!